Change of Basis

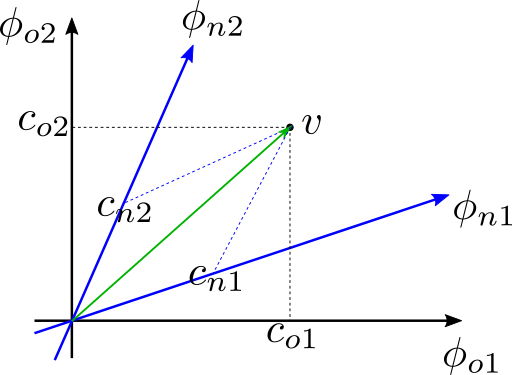

Any n-tuples/vectors in a vector space can be expressed as a sum of scaled basis vectors. The scaling factors are the coordinates of that vector. Lets say there is a vector \(v\) in \(R^2\). For a basis vector set \(B_o=\{\phi_{o1}, \phi_{o2}\}\) the vector \(v\) can be expressed as sum of scaled basis vectors.

\[v = c_{o1}\phi_{o1}+c_{o2}\phi_{o2} \\ v = \begin{bmatrix}\phi_{o1} & \phi_{o2}\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}c_{o1}\\c_{o2}\end{bmatrix} \\ v = \Phi_{o}C_o\]

the scaling factor \((c_{o1},c_{o2})\equiv \begin{bmatrix}c_{o1} & c_{o2}\end{bmatrix}^T\) is the coordinate of the vector. \(\Phi_{o}\) is the basis vectors as columns. If we choose a new set \(B_n=\{\phi_{n1}, \phi_{n2}\}\) as the basis vectors then the same vector is expressed with new coordiantes \((c_{n1},c_{n2})\equiv \begin{bmatrix}c_{n1} & c_{n2}\end{bmatrix}^T\).

\[v = c_{n1}\phi_{n1}+c_{n2}\phi_{n2} \\ v = \begin{bmatrix}\phi_{n1} & \phi_{n2}\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}c_{n1}\\c_{n2}\end{bmatrix} \\ v = \Phi_{n}C_n\]Now the question we are asking is, if we decide to use a new basis \(B_n\) for vector \(v\) whose coordinate vector is \(C_o\) for the basis \(B_o\) what will be the coordinate vector for the new basis \(B_n\)? This is easy to find by noticing the fact that the position of the vector \(v\) does not change with the basis chnage. So

\[v = \Phi_{n}C_n = \Phi_{o}C_o \\ C_n = \Phi_{n}^{-1}\Phi_{o}C_o\]Lets see what this equation says. \(v = \Phi_{o}C_o\) can be seen as a transformation \(\Phi_{o}\) that acts on the coordinate \(C_o\) to form vector \(v\). Similarly with \(C_o = \Phi_o^{-1}v\) can be seen as a trasformation \(\Phi_o^{-1}\) that acts on the vector \(v\) and spits out the coordiate.

\[\Phi \to v \\ \Phi^{-1} \to C\]With this interpretation it is now easy to express basis change in descriptive form. To get the coordinate in new basis \(B_n\) apply transformation \(\Phi_{n}^{-1}\) on the vector \(v\). The vector \(v\) is in turn expressed in old basis is \(\Phi_oC_o\). So the total transformation is \(\Phi_{n}^{-1}\Phi_{o}C_o\). The combined transformation on the old coordinate is \(P=\Phi_{n}^{-1}\Phi_{o}\). \(\Phi_{o}\) forms the vector, \(\Phi_{n}^{-1}\) returns the coordinate in new basis.

\[P=\Phi_{n}^{-1}\Phi_{o} \\ n \gets o\]It is now easy to change coordiante back and forth. To get the old coordinate from the new coordiante, apply \(\Phi_{n}\) to get the vector and apply \(\Phi_{o}^{-1}\) to return the coordinate. Total transformation \(\Phi_{o}^{-1}\Phi_{n}\) which is just the inverse of \(P\).

In the books the description is a bit different and it alwasy gets me confused. For example in 1 it says

The columns of the \(P\) matrix from an old basis to a new basis are the coordinate vectors of the old basis relative to the new basis.

To me it is quite convoluted and easy to get confused. Let see how these descriptions are equivalent. The old basis vectors can be expressed as scaled sum of new basis vectors.

\[\phi_{o1} = \Phi_{n}C_i \\ \phi_{o2} = \Phi_{n}C_j \\ P = \begin{bmatrix}C_i & C_j\end{bmatrix}\]The coordinates for \(\phi_{o1}\) and \(\phi_{o2}\) are \(C_i\) and \(C_j\) respectively wrt basis \(B_n\). According to 1 \(P\) is given as \(P = \begin{bmatrix}C_i & C_j\end{bmatrix}\). But I have said \(P=\Phi_{n}^{-1}\Phi_{o}\). These two statements should be equivalent.

\[\begin{bmatrix}\phi_{o1} & \phi_{o2}\end{bmatrix} = \Phi_{n}\begin{bmatrix}C_i & C_j\end{bmatrix} \\ \Phi_o = \Phi_{n}\begin{bmatrix}C_i & C_j\end{bmatrix} \\ \Phi_n^{-1}\Phi_{o} = \begin{bmatrix}C_i & C_j\end{bmatrix}\]Personally I think \(P=\Phi_{n}^{-1}\Phi_{o}\) is more intuitive. Also I do not need to calcualte \(\begin{bmatrix}C_i & C_j\end{bmatrix}\).